History of Periodical Illustration

Nineteenth-century illustrated newspapers published and republished thousands of illustrations, from the sensational to the mundane, the portrait to the panorama, which newly saturated the reading public with visual experiences, and effectively made the illustrated newspaper the progenitor of mass media. This section briefly describes the history of how newspapers and periodicals created and printed images, from the emergence of woodblock engraving to halftone photo-processes.

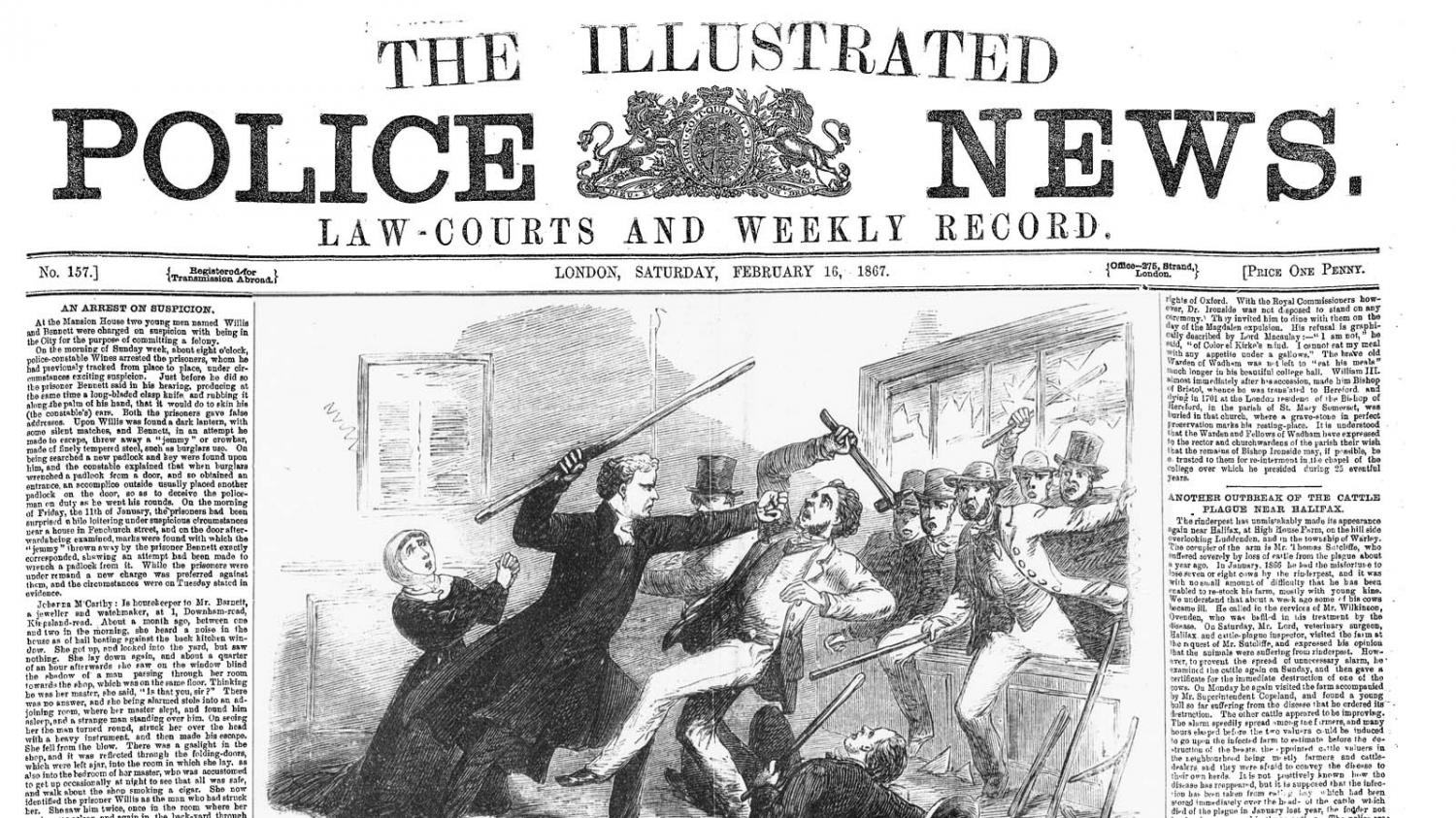

(Front page of The Illustrated Police News from February 16, 1867.)

The newspapers investigated in this project -- including The Penny Illustrated Paper (1861), The Illustrated Police News (1864), and The Graphic (1869) -- all used a technique called end-grain woodblock engraving. Ironically, when the industrial revolution came to the periodical press, it would have to abandon metal for wood to print illustrations at scale. Woodblock engraving was significantly developed by a British engraver, Thomas Bewick, at the end of the eighteenth-century. It uses squared sections of the trunk of the boxwood tree, so hard and densely grained that it allows two significant advantages for printing illustrations. First, lines engraved on the endgrain of boxwood (think cross section) can be much finer than previous woodblock techniques, which gouged out wood on the plank side. Second, these engravings can withstand hundreds of thousands of impressions in a press, far outlasting copper and even steel. Engraved woodblocks could also be set alongside type in a press bed (locked together in a form), thus allowing text and image to be printed together. Wood-engraved illustration was thus ideally suited for the economies of scale of periodicals as they rapidly expanded in the early nineteenth century.

One of the first periodicals in the UK to effectively use this technique was The Penny Magazine (1832), whose proprietor, Charles Knight, emphasized his magazine’s ability to bring useful knowledge and high-quality illustrations inexpensively to the masses. Perhaps the most famous periodical to adopt wood-engraved illustrations was The Illustrated London News (1842). In its first issue (pictured at right), the ILN loudly trumped the technique as offering “the very form and presence of events as they transpire, in all their substantial reality,” embodying “whatever the broad and palpable delineations of wood engraving can be taught to achieve” (“Our Address”). The ILN became a huge success, spurring competition from other illustrated periodicals, each of which sought to capture or expand the market. Our project’s three titles represent some of the variety of editorial goals of illustrated newspapers. The Graphic was launched as a direct competitor to the ILN, attempting to further ennoble wood-engraved illustrations as a form of graphic art, while also accepting contributions in other mediums from artists and the public (Thomas). The Illustrated Police News was a sensational Sunday paper, reporting crime news with somewhat lower-grade images but which are often more visually complex, blending multiple styles and textual elements in their illustrations. The Penny Illustrated Paper was among several to try to copy the ILN’s format while undercutting it with the Penny Magazine’s competitive pricing.

One of the first periodicals in the UK to effectively use this technique was The Penny Magazine (1832), whose proprietor, Charles Knight, emphasized his magazine’s ability to bring useful knowledge and high-quality illustrations inexpensively to the masses. Perhaps the most famous periodical to adopt wood-engraved illustrations was The Illustrated London News (1842). In its first issue (pictured at right), the ILN loudly trumped the technique as offering “the very form and presence of events as they transpire, in all their substantial reality,” embodying “whatever the broad and palpable delineations of wood engraving can be taught to achieve” (“Our Address”). The ILN became a huge success, spurring competition from other illustrated periodicals, each of which sought to capture or expand the market. Our project’s three titles represent some of the variety of editorial goals of illustrated newspapers. The Graphic was launched as a direct competitor to the ILN, attempting to further ennoble wood-engraved illustrations as a form of graphic art, while also accepting contributions in other mediums from artists and the public (Thomas). The Illustrated Police News was a sensational Sunday paper, reporting crime news with somewhat lower-grade images but which are often more visually complex, blending multiple styles and textual elements in their illustrations. The Penny Illustrated Paper was among several to try to copy the ILN’s format while undercutting it with the Penny Magazine’s competitive pricing.

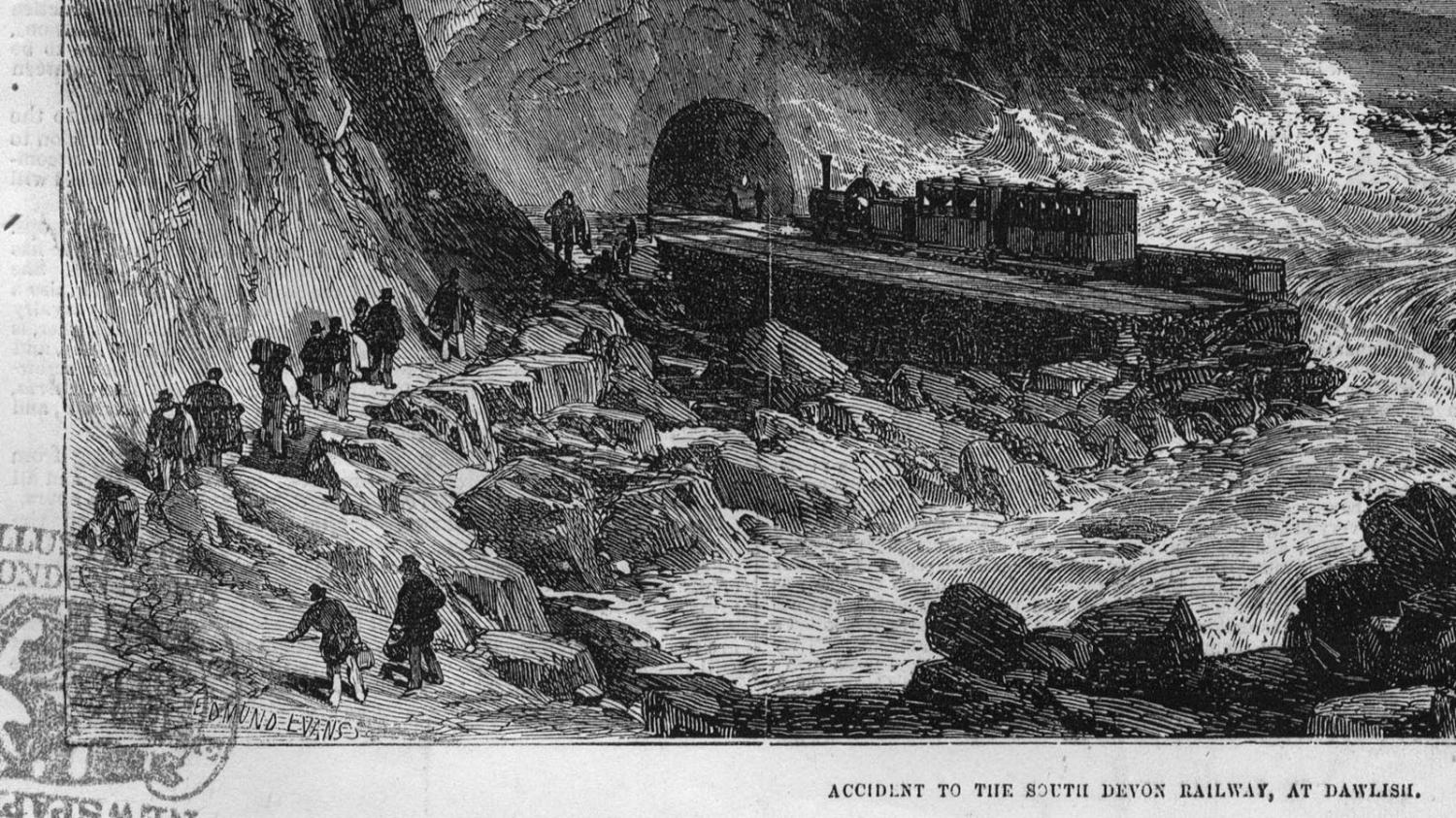

Wood-engraved illustrations went through several steps on their way to appearing in print. A typical illustration might start with a sketch or photograph, taken by an artist-reporter at a news event, or even a written description which adapts an idea (whether it was actually seen or not) to visual form. Illustrations were often made as composites of multiple sketches, offering a “synthetic” view which could provide more of a visual narrative (Gervais 381). Initial sketches were transferred to the wood surface by artist-engravers or, in later years, by exposing photographs directly onto them. Because boxwood is not a large tree, several squared blocks were often locked together for larger illustrations. These blocks could then be separated and distributed to several hand engravers at once who coordinated their efforts to carve out the negative space of the image. Once engraved, the blocks were reassembled and locked into a type form, either to be printed on a steam press, or else to be “copied” through a stereotyping process and recast as a curved printing plate, ready for faster production on cylindrical and rotary presses. Proof prints were usually taken before final printing, with press workers adding slips of paper under the block or the paper to be printed (called “underlay” and “overlay,” respectively) to correct or adjust areas of printing. Thus, while many periodicals represented their illustrations as visual facts, they were subject to a chain of interpretation, adaptation, and image adjustment all along their production path.

(Detail of an illustration showing engraved lines and the join of multiple blocks. Illustrated London News, March 3, 1855.)

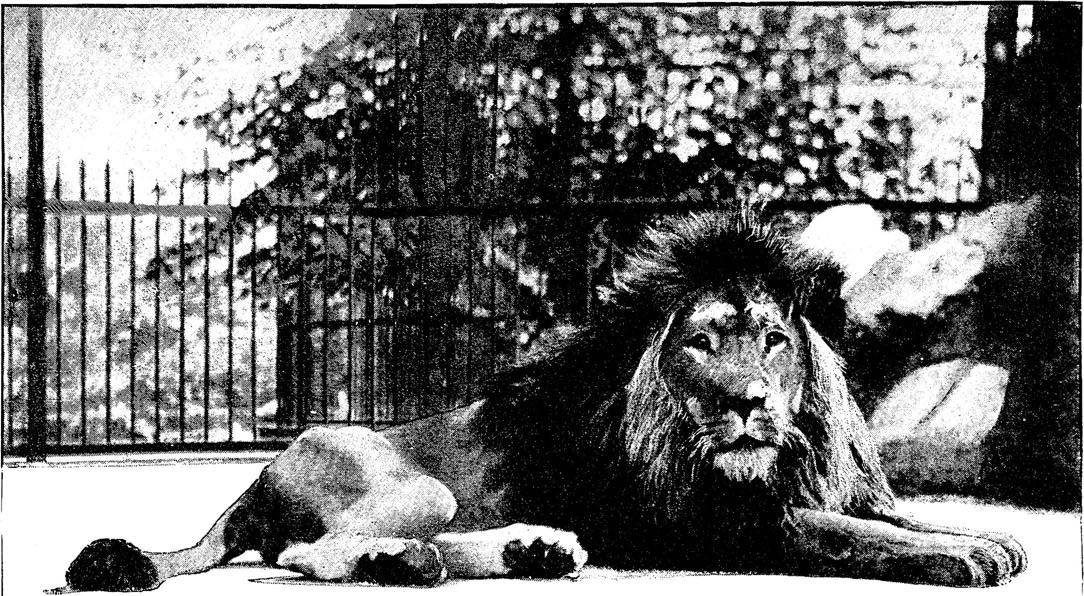

Nineteenth-century wood engravings may not induce modern audiences into such rapturous celebration as the ILN, but they offered an experience of reprographic fidelity which the Victorians received in terms which anticipate photography. Of course, wood-engraved illustrations and photography are not so distinct. As Gary Beegan demonstrates, these techniques were often used together, and photography was often used as source material for engravings. Photography in forms including daguerreotypes was already invented when wood-engraved periodicals became popular. But it wasn’t until the development of halftone techniques that periodicals could print photographic images at scale. Halftone printing exposes a photograph onto a sensitized metal plate through a screen of tiny dots. The plate is then chemically processed, as acid eats away areas which are “light” and leaves intact areas which are “dark.” The result is a relief plate whose raised areas can be inked and used to print a credible simulation of a photograph.

(Halftone print of a photograph of a lion in The Graphic, September 5, 1885.)

For mass-market periodicals, photo-reproduction processes took over from wood engraving by the 1890s. Again, these processes were never so distinct, but wood engraving was soon abandoned by the periodical press, for better or worse. For 50 years, it had been at the center of the newspaper’s development into a visual mass medium. For further histories and descriptions, see Korda, Sinnema, Barnhurst and Nerone, and Brake and Demoor in the project bibliography.