History of C19th British Newspapers

The newspaper in Britain precedes the nineteenth century, though a set of significant technological and demographic changes dramatically affected its evolution through the Victorian era, achieving a scale and saturation which may inaugurate the very notion of mass media. This was, as J.S. Mill proclaimed in On Liberty, “the age of newspapers, railways, and the electric telegraph.” They developed as a triad, together annihilating space and time -- as in the common phrase at the time -- to reshape Britain into a network of persons, texts, and transmissions. Newspapers loomed ever larger, too, in their role in public life. Writing in the quarterly Edinburgh Review in 1829, Thomas Carlyle complained that “The true Church of England, at this moment, lies in the Editors of its Newspapers.” Attending the cultural prominence of the newspaper were the gradual spread of voting rights, rising literacy rates, and cheaper access to periodicals, all of which were shifting the political landscape (to Carlyle’s chagrin). These changes are complex and not reducible to technological developments, though a few details are helpful to know in understanding the newspaper’s epochal rise to prominence.

The Industrialization of Printing

“Our Journal of this day presents to the Public the practical result of the greatest improvement connected with printing since the discovery of the art itself.” So starts an editorial in the London Times on 29 November 1814, announcing the first newspaper printed by a steam press. Steam power and industrial processes would profoundly change the manufacture, production, and distribution of newspapers in the nineteenth century. Though technologies are never solely responsible for dramatic historical changes, steam printing so increased the speed, scale, and affordability of the newspaper as to redefine it in modern terms. Because of their scale and the capital required to move to steam production, newspapers and periodicals far more than books or “jobbing” printing were printed by steam, including the Times and soon also numerous titles across the Atlantic. Printing presses would evolve into huge and complicated machines, with multiple paper feeding stations and impressions happening simultaneously.

("Richard March Hoe's printing press—six cylinder design." N. Orr, History of the Processes of Manufacture. 1864.)

Since the late eighteenth century, paper making had also become increasingly industrialized. The Fourdrinier process was among the best known, pounding the rag source materials, spreading the liquid “stuff” into sheets, then pressing and drying them. The demand for paper would soon put pressure on the supply of raw materials and, by mid century, cotton, linen, and hemp were giving way to wood pulp. Newspapers printed on rag paper could be big, tough, and withstand their passage through many readers’ hands. Though wood pulp was cheaper and became widely adopted, it would suffer in the long term from the acidic compounds it contains.

Paper production was also affected by taxes. With paper duties on individual sheets for newsprint, paper was made and sold in individual sheets, “stamped” once taxes had been paid. A more general “stamp duty” for any periodical containing news wasn’t abolished until 1855. These taxes were extremely controversial with an organized political response to eliminate them, as well as an active “unstamped” press of more radical resistance. The repeal of the paper duty in 1861 reduced costs for newspapers as well as allowed for paper to be produced, sold, and printed on continuous reels, rather than individual sheets.

Paper production was also affected by taxes. With paper duties on individual sheets for newsprint, paper was made and sold in individual sheets, “stamped” once taxes had been paid. A more general “stamp duty” for any periodical containing news wasn’t abolished until 1855. These taxes were extremely controversial with an organized political response to eliminate them, as well as an active “unstamped” press of more radical resistance. The repeal of the paper duty in 1861 reduced costs for newspapers as well as allowed for paper to be produced, sold, and printed on continuous reels, rather than individual sheets.

(Detail of a penny stamp on the Illustrated London News, 1855)

Faster, Cheaper, Better Connected

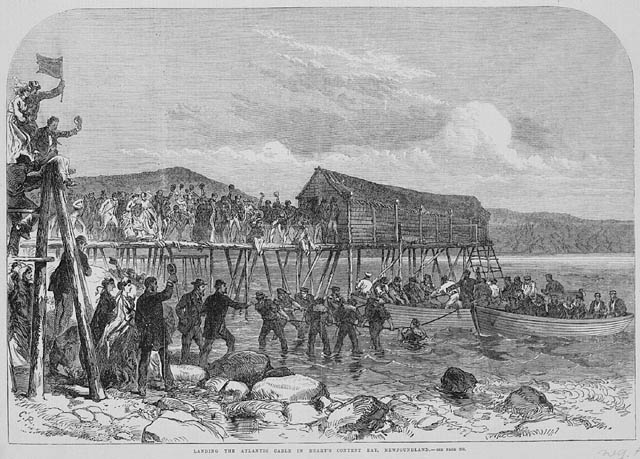

“News” also depends on novelty or the immediate reporting of events. Hence, many newspapers are named to emphasize the rapidity of getting to market, including references to their means of transmission (e.g. The Herald, The  Post, The Mercury, The Telegraph). The advent of railways in the 1830s rapidly sped up how information could be gathered as well as disseminated. Railways were shortly followed in the 1840s by telegraph wires which often ran alongside the tracks. Together, railways and telegraphs represented to many the “annihilation of space and time,” seemingly collapsing distant points to ready access. Telegraphic cables would soon expand their reach over land and water, with the first transatlantic cable laid in 1858 (it broke) and then permanently in 1866.

Post, The Mercury, The Telegraph). The advent of railways in the 1830s rapidly sped up how information could be gathered as well as disseminated. Railways were shortly followed in the 1840s by telegraph wires which often ran alongside the tracks. Together, railways and telegraphs represented to many the “annihilation of space and time,” seemingly collapsing distant points to ready access. Telegraphic cables would soon expand their reach over land and water, with the first transatlantic cable laid in 1858 (it broke) and then permanently in 1866.

(”Landing the transatlantic cable in Heart's Content Bay.” Robert Charles Dudley. Library and Archives Canada, C-066507. 1866.)

Telegraphy also changed the ways news had been conveyed and shared. Newspapers always relied on each other as sources of news. These relationships could be formal partnerships, as in exchange networks between editors, sharing their papers and reprinting news; they could be commercial services, as in centralized news agencies like Reuters, Havas, and the Associated Press; or they could be quite informal, a practice of “scissors and paste” journalism with widespread copying, sometimes credited, sometimes not. Scholars have been interested how these news networks functioned, considering how news was disseminated from metropolitan centers, how the liveliness of a provincial press uniquely sustained itself, how paragraphs and snippets and reports circulated internationally.

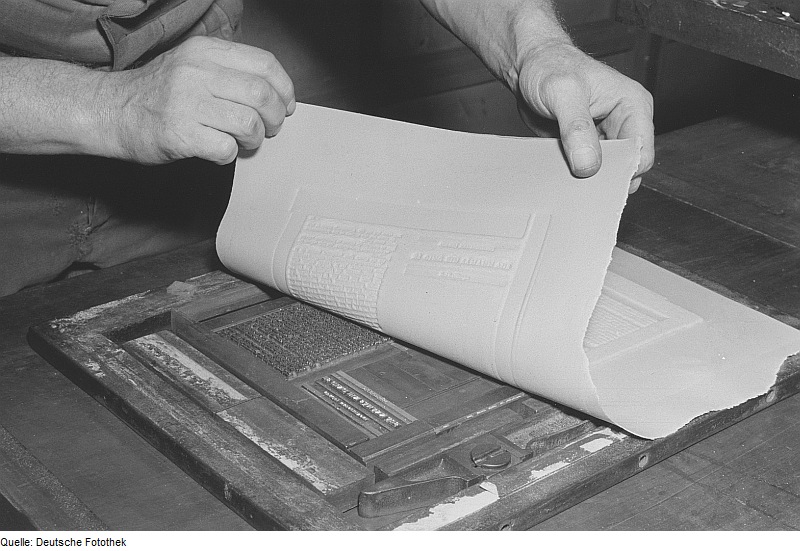

Designs of steam-powered printing presses changed over the century from the initial model of the “reciprocating” press, in which the printing bed moved back and forth, to “cylindrical” presses which allowed the paper to move in a single direction, speeding up the process. The “stereotype” process let entire pages of composed type be copied, either by an electrotype chemical bath, or by laying over paper maché to make a mold for casting another type form. Because the paper maché mold (the “flong”) was flexible, it could be used to mold type metal into a cylindrical printing surface, giving rise to the “rotary” press.

Designs of steam-powered printing presses changed over the century from the initial model of the “reciprocating” press, in which the printing bed moved back and forth, to “cylindrical” presses which allowed the paper to move in a single direction, speeding up the process. The “stereotype” process let entire pages of composed type be copied, either by an electrotype chemical bath, or by laying over paper maché to make a mold for casting another type form. Because the paper maché mold (the “flong”) was flexible, it could be used to mold type metal into a cylindrical printing surface, giving rise to the “rotary” press.

(Paper maché flong on a type form. “Herstellen einer Mater (Stereotypie).” Roger and Renata Rossing. Deutsche Fotothek, 1953.)

The Million Mark

Circulation rates for historical newspapers and periodicals varied considerably with their audience and distribution. Many Victorian commentators were amazed and alarmed by the proliferation of periodicals, which they called (not very approvingly) “reading for the million.” Literacy rates dramatically changed over the course of the century, and so did the genres of things for new readers to encounter. The latter decades of the Victorian era saw the emergence of the “new journalism”--an enlivened approach to reporting with more accessible typographical features, including the condensation of news into smaller tidbits. (A flag bearer for the accessible digest was the weekly periodical Tit-Bits.) By the end of the century, the new Daily Mail was selling one million newspapers a day.

The visual content of newspapers was also remarkably different. An issue of the Times from 1814 is a dense, five-columned block of imposing text. Illustrations came to the news in the 1830s and 40s, notably with the Illustrated London News and its use of wood engraving, a technique which made possible the industrialization of the printed image. Newspapers began to adopt halftone photographic processes in the 1880s which effectively replaced wood engraving as an image-making technique by the century's end. (See the History of illustration section for a brief introduction.) Typography had similarly become more visually diversified, including the use of “fat face” display type in advertising and emerging principles of graphic design evident in the new journalism.

Find further information about newspaper and publishing history in the project’s bibliography, especially Dodd, Banham, Williams, Brake and Demoor.