History of Newspaper Data

Just as important as understanding the history of newspapers is understanding the history of their passage through different media. Any digitized historical source has been shaped by how it has been produced, transmitted, stored, and transferred into other mediums. Data is never simply a surrogate for the original, but has been selectively “captured” according to certain goals and shaped by the processes of its remediation (Drucker). What sources were selected to digitize? What perspectives or histories do they include or exclude? How does the data structure enable or obscure ways of searching or accessing it? Researchers have to take these conditions into account when planning their study and considering their results. This section briefly considers the history of our project’s source data.

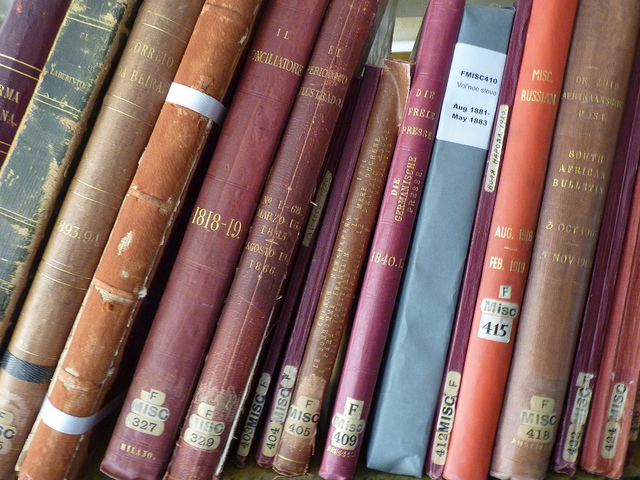

(Image credit: Luke McKernan, "Microfilms: Microfilmed newspapers at British Library Newspapers, Colindale, north London." 26 Sept 2013. Flickr. CC BY-SA 2.0)

The passage of newspapers from the nineteenth century into a database is not a simple story. Nor does it easily break down into the discrete stages below. But they are useful for understanding important moments in which newspapers were shaped into scholarly research collections.

Accession of Print

The first systematic attempt to collect British newspapers as such began with the British Museum in 1822. (The museum’s library departments would eventually become the British Library in 1973.) The British Museum made a deal to acquire copies of newspapers from the Stamp Office, then in charge of collecting taxes on newspapers. Even after the stamp tax was repealed in 1855, newspapers would be subject to “legal deposit” requirements, providing copies to the Inland Revenue Office. These copies were kept for a period of legal statute, then gifted to the British Museum. In addition to these papers, the Museum acquired other newspapers by donations and filled in gaps with purchases of sets.

Once at the British Museum, newspapers would be sorted, sifted, and bound in volume form. This proved to be a significant expense and would also put pressure on the museum’s storage capacities, resulting in the construction, in Colindale, of the Museum’s Newspaper Repository completed in 1905 (filled within 20 years) and the subsequent construction of the British Museum Newspaper Library in 1932. The Colindale facility was closed in 2010 with the British Library’s newspaper collections moving to a state-of-the-art facility at Boston Spa with its towering, dark, low-oxygen storage stacks.

Once at the British Museum, newspapers would be sorted, sifted, and bound in volume form. This proved to be a significant expense and would also put pressure on the museum’s storage capacities, resulting in the construction, in Colindale, of the Museum’s Newspaper Repository completed in 1905 (filled within 20 years) and the subsequent construction of the British Museum Newspaper Library in 1932. The Colindale facility was closed in 2010 with the British Library’s newspaper collections moving to a state-of-the-art facility at Boston Spa with its towering, dark, low-oxygen storage stacks.

(Image credit: Luke McKernan, “Various press. Bound newspapers at British Library Newspapers, Colindale, north London.“ Sept 26, 2013. Flickr. CC-BY-SA 2.0)

Microfilming

Microfilming emerged in the early twentieth century as a potential solution to the challenges of preserving old newspapers and storing copies more efficiently. Interestingly, the history of microfilming is tightly bound with intelligence interests and preservation anxieties during World War II. Threats to collections were underscored when, in 1940, an incendiary bomb hit the British Museum and destroyed a significant portion of the King George III’s collection. That same year, a high-explosive bomb hit the Museum’s original 1905 newspaper repository building at Colindale.

During a visit to the U.S. in 1944, the Director and Principal Librarian of the British Museum, Sir John Forsdyke, became convinced of the value of microphotography as a solution to the Museum’s escalating newspaper problem. The Museum sponsored Forsdyke’s visit to University Microfilms Incorporated (UMI) in Ann Arbor, Michigan, where he consulted with UMI’s founder, Eugene Power, about the equipment and facilities the British the Museum would need. In 1948, the Rockefeller Foundation sponsored three-month fellowships for British Museum staff to train at UMI on large-scale microfilm production, preparing to photograph the sprawling collections of British newspapers back in Colindale. When the Colindale facility rebuilt temporary structures in 1950, it opened a microfilm annex with four microfilm cameras donated by the Rockefeller Foundation, one of which remained in use through the 1990s.

(“Microfilming at Colindale began in the 1950s.” from Christina Duffy, “Read All About It #2 - Building a Future.” British Library Collection Care blog. January 13, 2014. CC-BY.)

Microfilming came with its own problems, including the use of acetone-based film which would eventually degrade, the difficulty of using large viewing machines, and the incessant challenge of storing yet-more copies of newspapers, however small in format. It is also difficult to say how much of the British Library’s collection of newspapers was filmed; estimates range between 5-30% of the print collection.

Digitization

The British Library’s initial efforts to digitize its newspaper collections in the 2000s were funded by a series of grants from the UK’s Joint Information Systems Committee (JISC). The proposed “British Newspapers 1800-1900” project had an initial target of 2 million pages. It was intended to be large scale, include significant geographical coverage, and be broadly useful to scholars, researchers, and the public. Because of contraints of budget and available technology, newspapers were not directly scanned to digital files. Instead, new microfilms were made of the newspapers to be digitized, and these films were subsequently scanned. The British Library partnered with commercial vendors to process the scanned images, separate articles into page zones, conduct optical character recognition (OCR) on the text, and build a searchable database for the collection. These partners included Gale Cengage and later Brightsolid, which continues to expand the collection as the British Newspaper Archive.

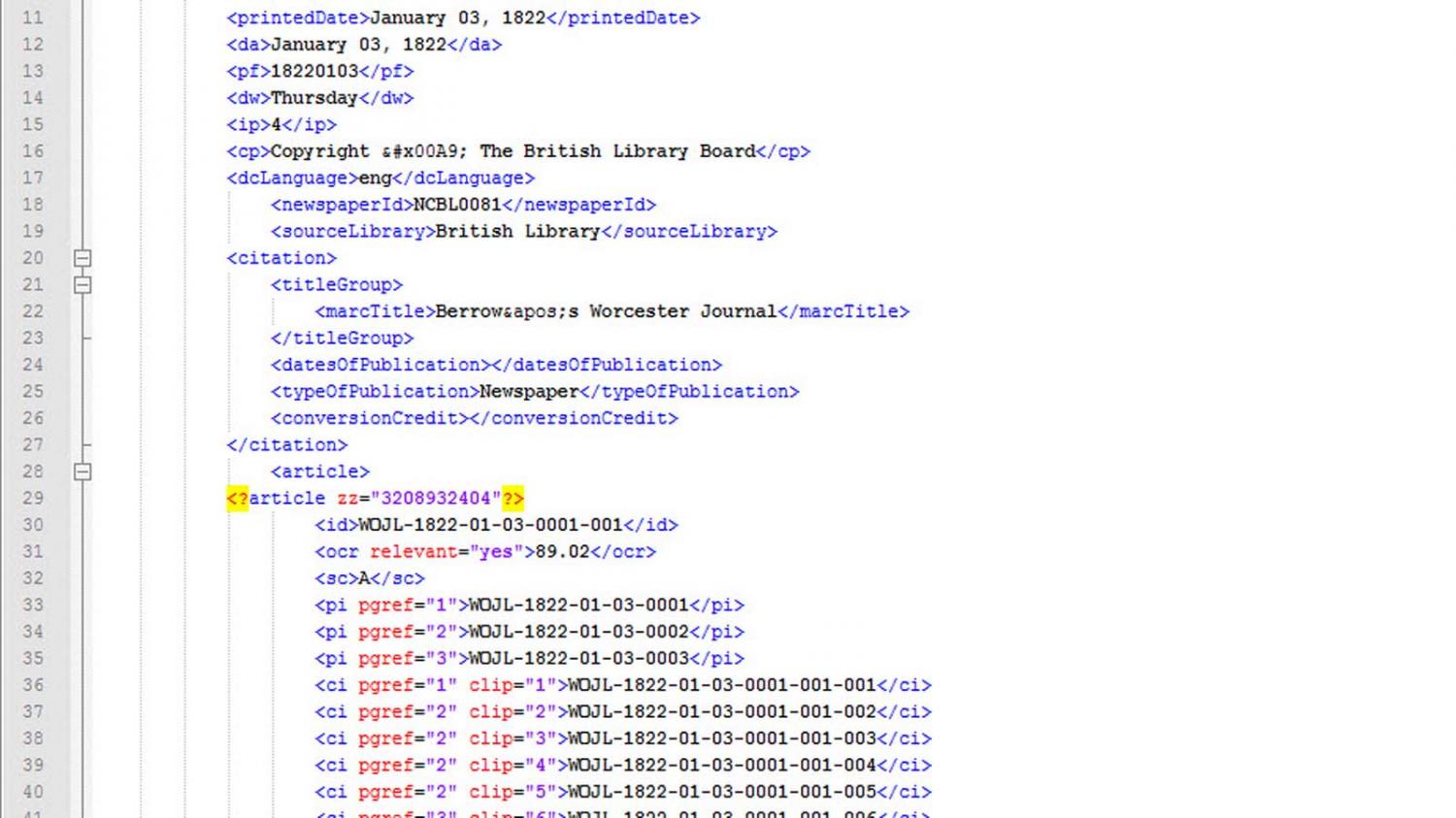

The data for the Nineteenth-Century Newspaper Analytics project derives from the “19th Century British Library Newspapers” collection (subsequently called “British Nineteenth-Century Newspapers”) which Gale Cengage licenses to institutions and academic libraries. The source files include high-resolution page facsimile images as well as XML files containing the text and metadata for each newspaper page. The collection as a whole includes semi-complete runs of 60 different titles, metropolitan as well as provincial. The data conforms to a “document type definition” (DTD) created by the British Library and Gale which establishes what kinds of things any file can include, such as metadata about the issue, data, article, title, category, &c. We have created an internal version of the data which scrapes away much of the tagging and sorts the text and metadata into a database for querying.

The data for the Nineteenth-Century Newspaper Analytics project derives from the “19th Century British Library Newspapers” collection (subsequently called “British Nineteenth-Century Newspapers”) which Gale Cengage licenses to institutions and academic libraries. The source files include high-resolution page facsimile images as well as XML files containing the text and metadata for each newspaper page. The collection as a whole includes semi-complete runs of 60 different titles, metropolitan as well as provincial. The data conforms to a “document type definition” (DTD) created by the British Library and Gale which establishes what kinds of things any file can include, such as metadata about the issue, data, article, title, category, &c. We have created an internal version of the data which scrapes away much of the tagging and sorts the text and metadata into a database for querying.

(An in-depth version of this history can be found in Fyfe, “An Archaeology of Victorian Newspapers.”)